Father Of Waters Lies Frozen

ON THIS COLD WINTER DAY, as the Father Of Waters lies frozen beneath an icy blanket, here is an excerpt from my summer essay, The Stick Throwers, from the book, “Deep Woods, Wild Waters.”

(It is a very big and strange universe in which we live, and we are surrounded by the unknown. We throw sticks from our tiny docks into a river whose beginning and end we cannot see, a river that flows endlessly into the misty blue sea of mystery).

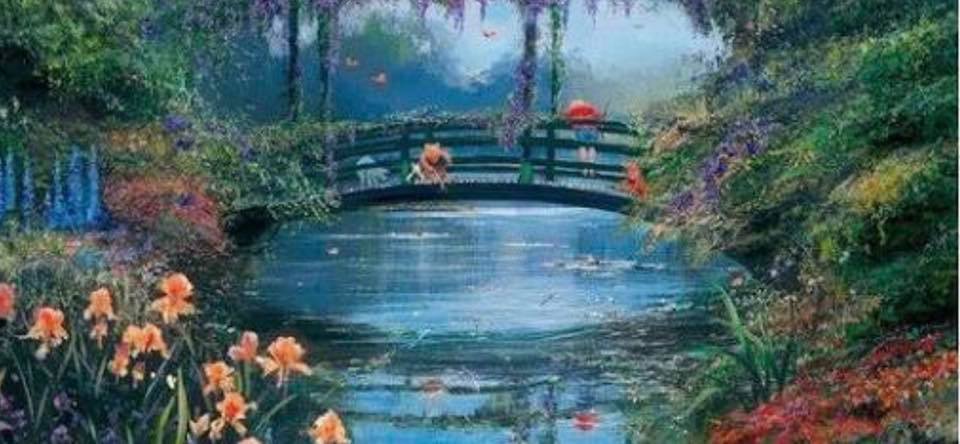

The little blond-haired girl and I stood on the small riverbank dock, throwing sticks into the water. For an hour or more we threw them, gathering them up carefully from the bank, placing them on the dock, choosing them one at a time. Throwing.

All manner of games, toys, puzzles, books, and other novelties and distractions waited back in the house. Any number of fun things to do. But we threw sticks into the river. For perhaps two hours.

It was her idea, of course. It is evidently deeply fascinating, when you are two, to throw a stick out into the water. To watch and hear it splash. To see it disappear for a moment, then rise back to the surface. To see the strange and beautiful ripples expand in moving circles. To watch the stick begin to move away, floating downstream.

One doesn’t know, when one is two, exactly how any of this happens. Exactly where all the sticks come from, and when and why they fell to the ground. One doesn’t know how the throwing works, beginning somehow with yourself, and ending far away. Why a splash looks and sounds the way it does and is so oddly satisfying. Where the ripples go. Where the sticks go when they disappear downstream. Where the river goes, and how it moves away even while it stays.

One doesn’t know these things, how they all work, when one is two. Nor when one is sixty-two. It is all an endlessly fascinating enigma, beginning and ending in wonder, bounded only by the riverbank, the small dock, and by a grandfather holding your hand so you won’t fall into the water…

As we stood there, bending and picking out sticks, watching their enigmatic flight, splash, and gradual disappearance downstream, I couldn’t help but think of an old childhood literary friend, Winnie-the-Pooh. On a very lazy sort of day, very much the same sort of day as ours, Pooh invented a wonderful game called “Pooh Sticks,” in which sticks were dropped into a stream, for the pure pleasure and fascination of watching them splash and float away. This was such a fine game on such a fine day that eventually many other friends gathered around to help play it. Roo and Piglet and Rabbit and Eeyore and all the others came and played, since it was apparent that very little was to be done on such a day that could compare with water, and sticks, and being outdoors on the edge of the Hundred Acre Wood.

How often I have thought, in interactions with kids and in the writing of children’s books, that all children are born naturalists. Every aspect of nature and the outdoors, when encountered with a young heart and open eyes, is ripe for fascination and full of meaning. And why not, for we evolved as an integral part of this same natural world. It is only when we are told, in a thousand, thousand ways, what is important and what is not, what is worthwhile and what is not, what is dirty and messy and dangerous and safe and useful and useless and valuable and worthless—and especially what things are already safely Known And Understood—that we begin to lose this wonder and joy…

A little girl playing by a riverbank seems to sense such things in an unspoken sort of way, that she is somehow a part of a mystical and wondrous world. And so, perhaps, does an allegorical bear playing beside the river. In Pooh’s story, Tigger gets a bit bouncy, as is his wont, and knocks poor Eeyore into the water, causing Commotion and Concern and the need for a Rescue. But eventually all is well:

“For a long time they looked at the river beneath them,

saying nothing, and the river said nothing too, for it was very quiet and peaceful on this summer afternoon.

“Tigger is all right really,” said Piglet lazily.

“Of course he is,” said Christopher Robin.

“Everybody is really,” said Pooh. “That’s what I think,” said Pooh.

“But I don’t suppose I’m right,” he said.

“Of course you are,” said Christopher Robin.

We are all stick throwers, tossing our sticks out into the water, our spaceships to the heavens, wondering what sort of splash they will make, where the ripples may go, how far the stick might float. And we cannot know. We are surrounded by mystery, and we cannot know. But we are all right, really. Of course we are.