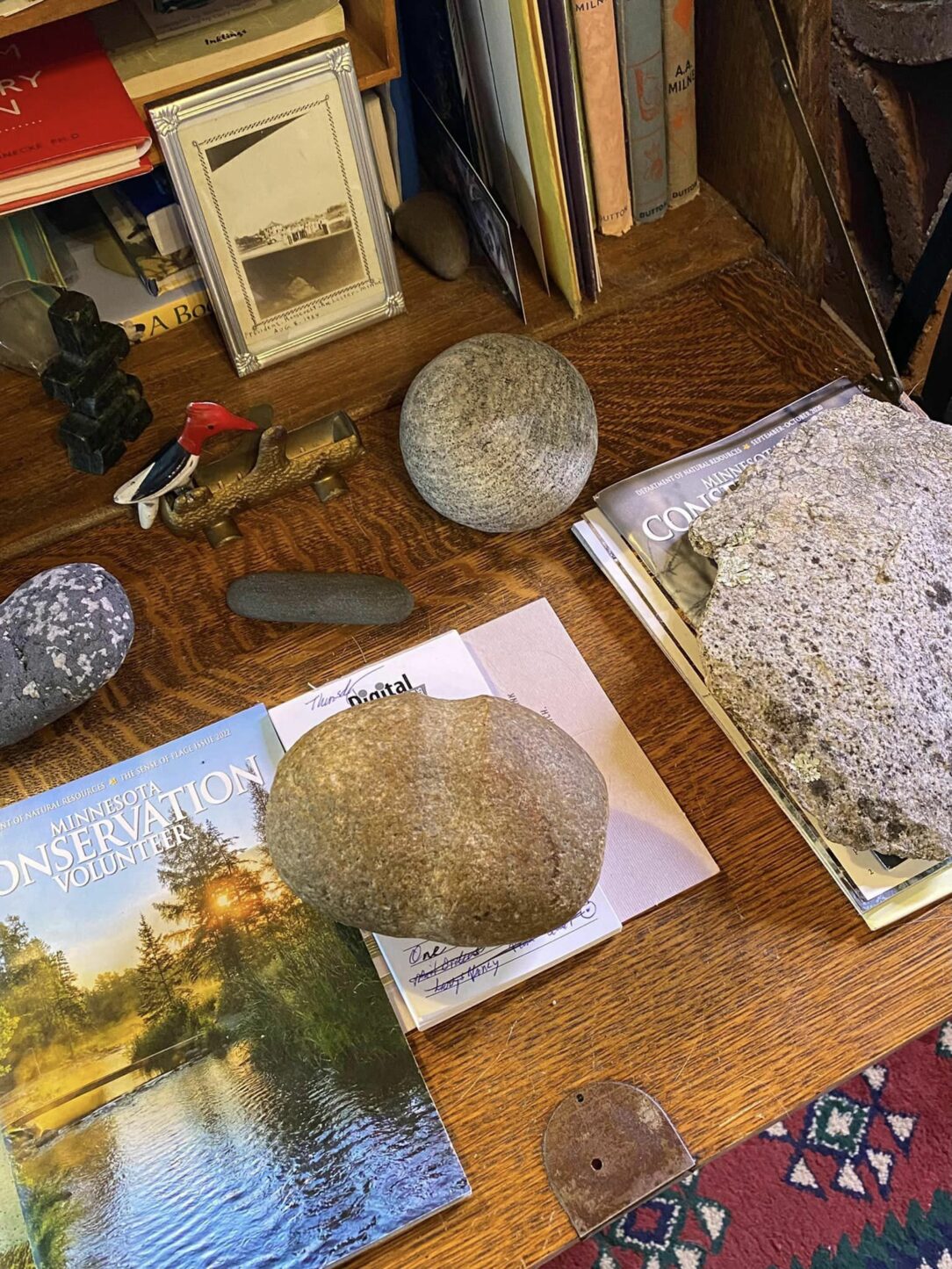

In My Writing Office

IN MY WRITING OFFICE there are many items of interest. At least to me. Hundreds of books, photos and art, mementoes from countless wilderness trips. But especially… rocks. Rocks have been important to me since earliest childhood. And I suspect I am far from alone in this regard. The following chapter from my book, ‘Deep Woods, Wild Waters,’ (University of MN Press) explains my attachment to these messengers from the earth. It’s called ‘The Gospel of Rocks.’ (Look closely and you may find some of the stony friends mentioned in the story).

An unknowing visitor to my office might imagine me to be a geologist, rather than a writer and musician, for rocks perch everywhere you look.

To be sure, other items and mementos populate the room as well. One is an old, framed photograph of my great grandparents, with my dad Jim and his brother Dick, all proudly leaning against the front bumper of a brand new, 1927 Pontiac parked in front of “the farm” near Douglas, Minnesota.

Photos of my grandmother and grandad and Aunt Mary smile from near the window. Sigurd Olson surveys the scene from an Alfred Eisenstadt portrait by the doorway. Albert Einstein studies a paper in one photo and rides a bicycle in another, reminders to work hard and to have fun.

Abraham Lincoln pores over a bit of prose with pen and paper, a silent advisor about seriousness of purpose, responsibility, wit, and the power of words. And other things I can’t quite name.

Photos show our two boys as children—Eric on my knee under a crimson sunset, Bryan holding my hand as we walk down a forest path together—and our two grandchildren, Maya and Henry.

On my writing desk rests a vintage copy of “The House At Pooh Corner,” with a small, stuffed Pooh sitting thoughtfully beside it. On the walls around the desk are mounted replicas of large fish, reminders of glorious moments in the life of a fisherman. I see a baseball signed by Bob Gibson. A Norman Rockwell calendar painting from 1953. And of course, walls and shelves are lined and piled and stuffed to overflowing with books.

On my writing desk rests a vintage copy of “The House At Pooh Corner,” with a small, stuffed Pooh sitting thoughtfully beside it. On the walls around the desk are mounted replicas of large fish, reminders of glorious moments in the life of a fisherman. I see a baseball signed by Bob Gibson. A Norman Rockwell calendar painting from 1953. And of course, walls and shelves are lined and piled and stuffed to overflowing with books.

But mostly, I see rocks. Rocks stand as doorstops. Rocks serve as bookends and as paperweights. Rocks line the windowsills to catch the sun. Rocks lay around just taking up space.

I am not a geologist, of course. A disorganized mind coupled with an inability to count much beyond double digits seemed to limit my career as a scientist. But I have always loved rocks. The fascination may have begun as I trudged home from the second grade one day in Sioux City, Iowa, past a construction site that was being bulldozed. The machines were parked; no one was around. There, protruding from the dusky yellow “loess” soil characteristic of northwest Iowa, was a large, rounded stone. The stone had a deep groove worn all the way around its center, something which even to my six-year-old, untrained eye looked unnatural. I somehow knew that it was significant.

I picked up the heavy rock, carried it home and kept it. I believe I later brought it back to school for “show and tell,” and somewhere along the way I became aware that it was very old, that the groove around the stone was used to attach a handle, and that it had once been some sort of club, or hammer.

Years later I did more in depth research, discovering that the granite artifact probably dated from the Archaic era in North America, lasting from ten thousand to three thousand B.C.E., and that it was a common “ground tool,” created when a hard, igneous or metamorphic rock was pecked at and gradually shaped, then smoothed with an abrasive material like sandstone. The stone was then attached to a split wooden handle, the top of the handle bound together with fresh animal sinew. As the sinew dried, it tightened until the stone was held in a vise-like grip. It could have been either a war club or a hammer, or both, the distinction being primarily one of use.

But long before I learned these things and understood what they meant, indeed all through my childhood, that rock already meant something to me. It symbolized the long, slow passage of time. It spoke of mysterious things, of secret stories that could be learned if one could but understand the language. Not only the stories of the ancient people who may have shaped the stone, but the even older stories of the stone itself, where it came from, and how it was formed.

Other rocks filled my childhood as well. One day, out in the alley behind the house, up against an old garage, I saw something sparkly sticking up out of the dirt. Digging it out, I found a beautiful, pyramid-shaped stone, the sides covered with small, green crystals, topped with a milky white cap. I had no idea what it was, but it was pretty. Who knew why it was there, in the dirt beside the garage, but clearly no one else cared about it or recognized it as a treasure.

I did. The green crystals could have been some sort of diamonds and probably were, or maybe emeralds—I was pretty sure emeralds might be green. And besides the possible monetary considerations, there was the pure beauty of the thing, and the fact that it looked very much like a tiny mountain, with sparkling green, forested sides and a snow-capped, quartz top. Who could say what such a thing might be worth? It was worth a lot to me, and became the centerpiece of an ever-growing boyhood rock collection.

My collection included striped agates and flint arrowheads, a chunk of iron pyrite—fool’s gold — and many rocks I did not know the names of. Of particular joy to me was a pile of snowy white granite stones, probably two to five pounds each, flecked with large flakes of mica, all of which had been gathered and lugged by me from a rocky point at Lake Kabetogama and stuffed into the trunk of my grandad’s sedan for the trip home, a trip he cautioned me the car would likely not survive due to the enormous extra load. But they were the prettiest rocks I had ever found, and I could not leave them behind. We did make it, barely according to Grandad, and my rock collection continued to grow, month by month, year by year. Until after several changes of address and rounds of packing and unpacking, it was suddenly, mysteriously, gone.

I never did learn how or why, whether it was just an accident or if perhaps my mother simply grew weary of dealing with boxes of rocks. I mourned the loss of my treasures, particularly the stone hammer and the green crystal pyramid. Decades later I found, in a museum rock shop, a hammer-stone, nearly identical in weight, shape and size, to replace the lost one. It now holds down papers on my desk, lest they become obstreperous or unruly. The green pyramid with the quartz top—I never found another like it. In fact it could be that my entire office, deck, and yard-full of rocks is merely a lifelong attempt to reconstitute that lost, boyhood rock collection.

Years later, in college, I took a geology course. But the way the professor looked at rocks and the way I looked at rocks did not seem to have much in common. Probably I just didn’t have the ears to hear or the eyes to see at that point. It wasn’t until years after college that I began to learn from my good friend Mike Link, a gifted and passionate naturalist and teacher, how to truly look at a landscape. I began to see stone and soil, hill and valley, prairie and river and lake and wetland, as an ancient and continuing story of many chapters, a mystery to be solved and decoded, following the clues that glacier, wind, and water had left behind.

How satisfying it was to begin to understand the story of glaciation, particularly the impact that the recurring epochs and their divergent lobes had on the state of Minnesota. The Canoe Country became even more meaningful and intriguing as I learned that the myriad islands and rocky points I loved so much, even my treasured white granite point in Kabetogama, (actually, something called “granodiorite”) were all a part of a vast upland area called the Canadian Shield, or the Laurentian Peneplain, covering an area of 3 million square miles. The remaining bedrock formations were in fact the worn-down roots of a mountain range, over 3.9 billion years of age, once taller than the Himalayas, stretching from Greenland to the Adirondacks, Minnesota to the Northwest Territories.

Beginning to see the landscape as story helped me more than ever to comprehend my small place in it, and to feel a sense of perspective that helped to leaven the rush of daily life.

Beginning to see the landscape as story helped me more than ever to comprehend my small place in it, and to feel a sense of perspective that helped to leaven the rush of daily life.

But mostly, I remained a humble rock-collector. Rocks are fine things to collect. They are slower and easier to catch than birds, and are thus superior to feathers. They are heavier and better for holding things down and propping them up than wood or stamps or coins. They are cheap, even free, if you find them yourself. And they are wonderful reminders and tellers of stories.

Glancing up from my writing desk, I can look in any direction and see old friends, remember adventurous trips and resonant stories. On my desk is a new series of field guides I haven’t gotten to yet, held up on one side by a chunk of pink pegmatite from the coast of Maine, and on the other by a hefty piece of white Kabetogama granite, a replacement for the old lost ones. Leaned against them is a Petoskey Stone from Lake Michigan, 300,000,000-year-old fossilized coral from an ancient sea. Near that is a piece of petrified wood from a long-ago tramp through the Rocky Mountains near Yellowstone, and when I pick it up and hold it I remember the excitement I felt when I first discovered it.

There are three wafer-like red rocks from one of the sedimentary layers of the Grand Canyon, and rubbing their rough texture I still recall the impossibly tiny thread of water at the bottom of that vast stronghold of stone, the easy walk down and the surprisingly longer walk back, and the sudden appearance, on great motionless wings, of the condors we had been waiting three days to see.

At the far end of my office, propping open the door, is a large geode, one of several from a grand day of rock collecting with my friend Judy in a ravine near Keokuk, Iowa. I still remember the thrill and suspense at finding these chalcedony eggs of the earth–each one plain and brown and unimpressive on the outside–and waiting with bated breath to see what sort of inner fairyland cave of crystals would emerge with just the right tap from a hammer.

I see my Holy Island rock, a wave-washed sphere of rose quartz from England’s North Sea coast; my Katherine Hepburn rock, a smooth, gray granite orb from a stony beach near Fenwick on the Long Island Sound; and my Listening Point rock, a gift from Sigurd Olson on the shore of Burntside Lake.

In a lifetime spent gathering rocks, I’ve learned that waterways and rivers, lakes and oceans, are among the best places to find them. Water carries away the soil, exposing gifts that may have lain buried for centuries, for eons. Water is a natural polisher, and given enough time will smooth any rough stone into a keepsake fit for a hand, a shelf, a pocket. To find a rock in the water is to see it at its best—shiny, every feature enhanced as if by lacquer. Sometimes I will pick up a rock from its place on a shelf or desk and take it to the water faucet, just to see it again as it was when I first found it.

Visual appearance is not the only thing enhanced or retrieved by water. On one bookshelf, near several volumes on Winston Churchill and beside Einstein on his bicycle, is a nondescript, brown, sedimentary stone, pockmarked and rough. It came from an eroded creek bed under the redwoods in northern California. Standing among those giants one is, of course, struck by the visual majesty of towering columns disappearing into the mists overhead. But another sense was awakened on my first visit years ago.

Wandering among the giants with their mighty, furrowed trunks, craning my neck to glimpse their tops in the canopy overhead, I was also aware of a smell—the rich, moist, earthy scent of the forest floor, of millennia upon millennia of ocean mists, of decomposed ferns and mosses and fallen redwood trunks. It was the scent of the damp, rocky ground itself, and I breathed it in deeply, wanting to remember it. The sense of smell, it has always seemed to me, is our most powerful aid for recalling a memory, revisiting a place and time. Modern research seems to bear this out. In any case, once in awhile, when I want to return to the redwoods, I pick up that small rock from the creek, take it out to the kitchen faucet, and let just a drop or two of water fall upon it. That is all it takes. Holding it up to my nose, I breathe in the scent the water has released, the same aroma I smelled long ago among the redwoods, and I am there once more, walking those dim aisles among the giants, hearing the faint tinkling of the creek.

I have paddled riverbeds of granite, limestone, and sandstone, each bedrock giving a river a distinctive color, its own vibrant character, with different configurations of falls and rapids. I have camped on outcrops of 3.5 billion year-old greenstone, three quarters as old as the earth itself, and looked up from there in awe at a 14 billion year-old universe. I’ve listened to night waves pounding a black, basalt shoreline, knowing that it will take eons to wear away an inch. I’ve stood in wonder beside a wilderness waterfall, watching half of it disappear into a great hole in the earth, then finding where it emerged again a quarter mile distant. And in each case I’ve picked up a stone to remind me of the place.

All of my rocks, gathered or left behind, remind me that important things take time. A lot of it. That the universe and this world evolve by long, slow processes. That change is often incremental and evolutionary, and barely visible to the eye of short-lived human beings. That we are surrounded by mystery, by beauty, by forces and processes beyond our control. That much of the sturm and drang of newsprint, internet, social media, and the daily obsessions of popular culture is pointless silliness. That some things in life are solid. And firm. And safe to build on. But you have to look carefully to find them.

In my office, on my writing desk, one more rock occasionally tugs at the edge of my attention, and I’ll sometimes pick it up in an absentminded sort of way. It’s a smooth, oblong, rounded stone from the ocean coast of the Olympic Peninsula, black as midnight, worn and shaped by billions of waves. I like to hold it sometimes when I’m writing, or simply wondering or imagining. It’s hard to say why. I just like the way it feels in my hand. Enough reason for a rock collector.