Stop to Ponder

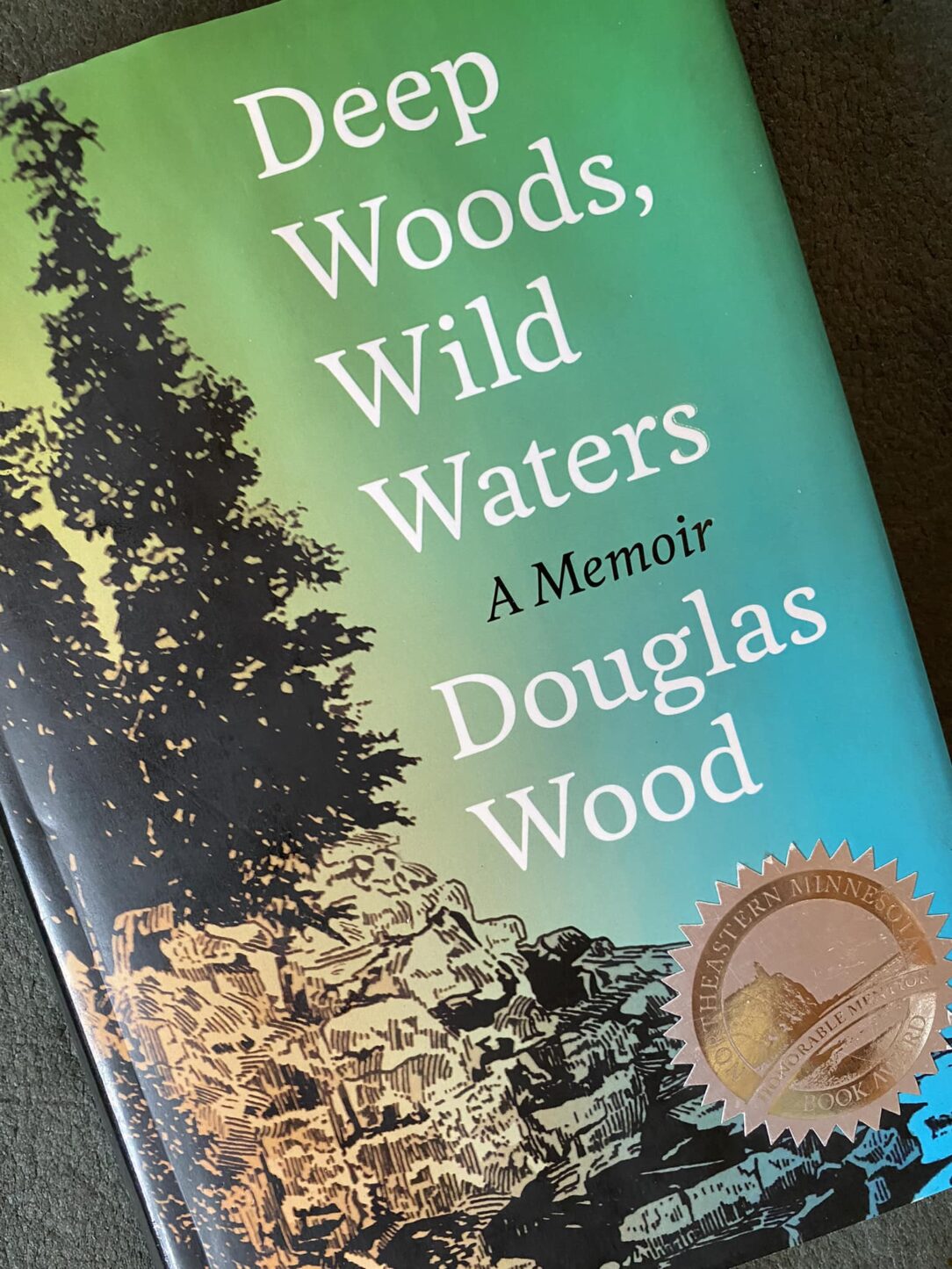

SOMETIMES WE STOP TO PONDER why we do the things we do. For many years I have led folks on journeys into wild country. In the form of ‘Road Scholar’ trips, I still do. From my book, ‘Deep Woods, Wild Waters,’ here’s why. The essay is called, “Hello To Life.”

I stood in the great, billowing mists of a tremendous waterfall in the far north. We had paddled and hiked a long way to get there and when we arrived a strange feeling came over me. Shirtless, cold and wet, I raised my arms high in celebration, remaining planted there on a great slab of granite, gripped by a fierce and primitive joy in the roar and the thunder, in the power of the falls and the feeling of the icy mist in the warm sun; all enhanced by the knowledge that nothing significant had changed about this wild and glorious place for millennia. It had not been tamed or “improved.” No spotlights lit up these falls at night. No crowds stood behind guardrails or sipped drinks from the safety of tables behind windows. Here was only the timeless thunder of wild water over stone, the spray rising in great clouds towards the sun, soaking the spruces and jackpines and rocks. Standing there, arms aloft, soaking wet, I somehow felt a part of it all, felt as if I had traveled a very long way to arrive at someplace that felt like… home. Eventually I turned around and saw the entire group, arms raised, drenched in the rainbow-hued mists. It seemed all had felt the same sensation, responded to the same wordless call.

This feeling of coming home is not uncommon in the wilds, for it is a homecoming in the truest sense—a return to a beautiful land still remembered, still present in the subconscious. When you arrive home after a long time away it is also not unusual to encounter a familiar person—an old friend perhaps—someone you once knew well, but have lost track of somewhere along the way. But it can come as something of a shock to realize that the someone you’ve lost track of is the person living inside your own skin.

And that can be a good place to start—your own skin. I have often spent days, even weeks on canoe trips wearing little more than a pair of cut-off jeans. Crawling out of the tent first thing in the morning and plunging into a cold river or lake puts you rather quickly in touch with the real world and your place in it. Having your bare back showered with rain, or waterfall spray, and a few minutes later that same back drying in the sun and the wind, reminds you that you’re a living creature, with all that simple fact entails. Watching your hide turn from pink and white to brown and copper, knowing that the color didn’t come from a spray can or a light-closet, gives you the sense that you are physically a part of the world around you, unencumbered by barriers.

A nice lady once asked me in alarm, “Don’t you ever wear sun-block?”

“No…”

“Well, why not?” she persisted.

“It blocks the sun,” I answered.

A foolish reply, perhaps, and I may one day regret it. But I crave the feeling of skin being in touch with the natural world rather than protected from it. And when the weather turns cold and the shirt and the wool mackinaw come out of the pack, it is equally a pleasure to consciously notice the warmth and comfort a friendly old garment provides; while the fact that it smells of old campfires and makes a poor fashion accessory in no way detracts.

The simple, sensual pleasures of time in the wild are among the least remarked but perhaps most important elements of the entire experience, returning a person to a genuine awareness of the natural creature he or she is.

Often the sensual stimuli are subtle—less majestic than a waterfall perhaps, but no less important. There is great satisfaction in picking a likely, level spot for a tent, clearing it carefully, and setting up for the night. In knowing you that you have a little “home” of your own creation and are safe from the elements. Once, far in the bush on a little-traveled river, the time came to make camp, but no open clearing or granite outcrop could be found. What we had found was a good fishing hole and we wanted to camp nearby, perhaps stay an extra day. We landed the canoes on a spruce covered point that had been hit several years earlier by a windstorm. Tree trunks were jack-strawed one upon the other, the entire place a jumbled mess. But with our fishing hole in mind we got quickly to work with sven-saw and axe, and in only an hour, deadfalls were cleared and a pleasant camp created, complete with free-form benches and chairs and tables. Where the downed trees had been piled were now exposed lush layers of moss. And after a fish-chowder supper and a few sips of “special ingredient,” we slept better than was even our normal custom, cushioned by soft mattresses and pillows that had been trapped only hours before beneath the deadfalls. Muscles and joints aching and sore from days of paddling and carrying felt pampered and swathed in comfort. And we had the added pleasure of knowing that someday other tired souls would come along and find a good campsite. Per North Country custom, we left a small pile of split wood, a scrap of birch bark tucked under one corner.

It is good to feel the importance of small things, to devote care and conscious consideration to items that in normal daily life would never be given a second thought. That little scrap of birchbark. A book of matches. A favorite pocket knife that can be pulled out at a moment’s notice, always kept sharp and ready for duty. A whet-stone. A hand-carved peanut butter paddle. A length of rope tucked into a particular corner of the pack. The old hat that doesn’t repel the sun or rain as well as it once did, but has become essential. A simple sewing kit. A camp saw. Even a camp rag. Small items such as these, with a total value of less than $100, take on a value and meaning far greater than things worth a thousand times more back in town—provide in fact a daily meditation on what is really important and vital in life. Sometimes life itself can depend upon them.

In the bush, nothing is taken for granted—everything must be either earned or created or carried or saved or built. And in every step of the creating and building and carrying you are subtly reminded of the real identity of the creator-builder-carrier—that person inside your skin. This is an inherent identity that has nothing to do with titles, resumes, or bank accounts, career failures or promotions or awards. In the wilderness, such things are of no consequence—all that matters is how we relate to one another and accomplish the task at hand.

This aspect of true community is one of my favorite features of wilderness travel. For me, everything began with an insatiable hunger to be “in the wilds,” discovering and exploring the natural world, and that desire never abated. But to my surprise in the practice of guiding, I honed a keen and ever-deepening interest in people and human behavior, even returning to school to work toward a master’s in psychology. Certain observations became apparent early on, and were repeated many times over the years. Those who talk the loudest are often the most insecure; those who profess to know the most often have the most to learn, and the hardest time doing so; those with the most macho trappings—big sheath knives and fancy outfits and a professed desire to “bring my gun,” are usually the most anxious; and in general—in general, mind you—women are far less trouble in many of these regards than men.

But generalities are just that. Each person is unique, blessed and burdened with his or her own qualities, backgrounds and abilities. And it is the process of getting to know unique individuals—what makes them tick, what they love and how they grow—that has been a continuing and unexpected joy. As a shy but observant child, growing up in a college professor’s family with occasional social events, concerts and dinner gatherings, I often thought I saw people “putting on airs,” stuffing shirts and filling out suits, seemingly impressed with themselves and their place in the world. And I remember habitually thinking, “I wonder what he’s really like under that suit?” And, “Why does she act that way?” And, “How would he do in a fishing boat on Lake Kabetogama?” And if my answer was, “He’d be hopeless,” I was left unimpressed. I developed a wide and deep streak of egalitarianism, a feeling that clothes definitely do not make the man or the woman; and that under the suits and under the skin, we’re all pretty much equal. Except for the guy who thinks he’s special.

As a canoe guide, I found the perfect laboratory to test these youthful theories, and learned I wasn’t far wrong. Camp life is a crucible. When the expensive suits are left in the closet, when the impressive resume is left in the office; when the folks who admire or flatter you—or conversely who remind you daily that you’re not worth a damn—are left behind, then you have the chance to find out who you really are. When most of your possessions are far away, it is possible to discover what you really need. And if you are a supposed big-shot and you find that the housewife, the custodian or the kindergarten teacher is handier in the woods, in the canoe and in camp than you are, it is possible—it is necessary— to determine what sorts of life skills are really important. Sooner or later everyone realizes that the only way to sit around a campfire is in a circle, no seat higher or more important than another. In the wilderness the only status that matters is as fellow members of a community, our true value discerned only as companions, helpers and friends. Simply being a person of good cheer and good humor, quick to spot a need and help, slow to anger or take offense—on the trail these are qualities prized above all others. And coming to realize that being “a success” means only one thing—helping the group as a whole to succeed—is the ultimate understanding.

Sometimes in the big world it is easy to forget such things, to buy into what others may think of us, to forget our deepest selves and deepest values. It is a world filled with constant distractions—in the most literal sense of the word. Innumerable media and devices, technologies and entertainments, sounds and furies surround us—all specifically designed to distract us from our real lives and relationships, from our pain and joy, grief and growth, from what it feels like to be a human being, alive on planet earth. I have always had a hankering to know that essential feeling—to rediscover it again and again, to try to understand it. I have been lucky to share that quest with others who feel the same imperative.

We live in what is sometimes called the “Information Age,” yet much of the information we encounter is counterproductive, leading us not toward self-understanding but away from it. In wild places another sort of information awaits us—information that speaks to the subconscious and to some green and living place within, information that leads one back to the elusive self. In noticing the shape and silhouette of a pine or cedar, how it has grown for 100, 200, 300 years, we can—without even realizing it—inform our own growth, our own decisions about how to proceed in life. Putting one’s hand on a two billion year-old boulder, a silent presence that has remained unmoved from the place the last glacier dropped it 10,000 years ago, can help put troubles and triumphs into perspective. Birds, fish, wildlife, the flowing of water and the movement of clouds, the rise and fall of landscape—all these elements reflect and mirror the landscape within, and help to bring it into focus. This is information that doesn’t make the news, but does remake the soul.

At least that is how it has often felt to me when paddling a wild river or carrying a long portage; when waving smoke from my eyes while sharing a campfire circle with friends; when crawling out of a tent at dawn, rubbing my back from a rock or a root that I somehow missed when setting up night before. Or when standing in the billowing mists of a thundering waterfall, celebrating the simple fact of its existence, and of my own as well. It is at such moments that I sometimes say hello. Hello to that fellow I’d missed for a while. Hello to life.