WHEN I WAS A BOY

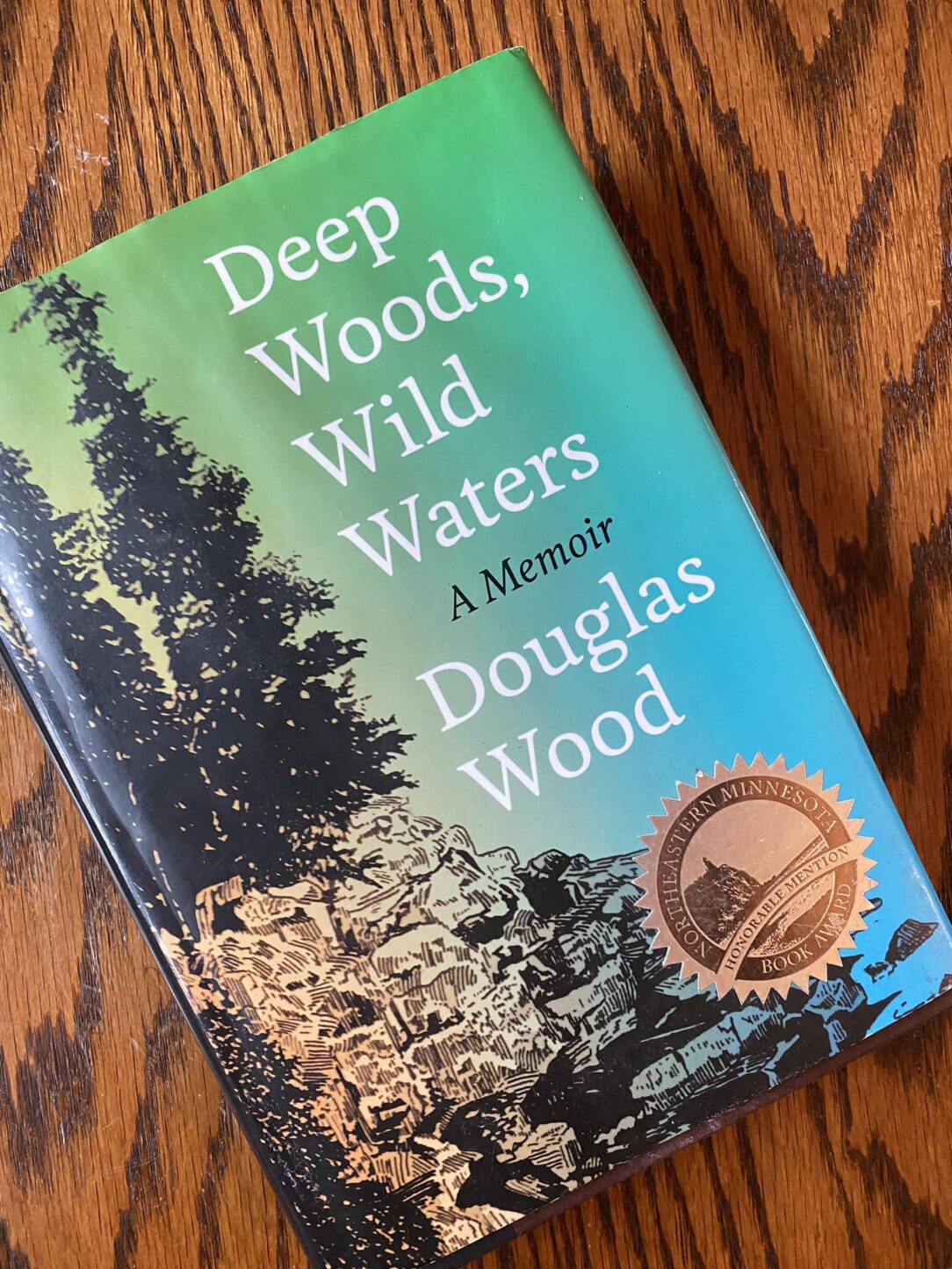

WHEN I WAS A BOY, every summer had a 2 week slice of heaven built into it. That was the time our entire family gathered in a cabin on the shores of a beautiful northern Minnesota lake called Kabetogama. Time away from important jobs and studies and school and stuff that I hated, and close to lakes and loons and pine trees and stuff that I loved. Including my beloved grandad. When I was ten, while at Kabetogama, Grandad gave me the coolest gift I ever had, a ‘genuine’ Royal Canadian Mounted Police sheath knife. This little excerpt from my memoir, ‘Deep Woods Wild Waters’, is about that knife (which I still have, pictured below) and other things. It speaks of a huge lake, stretching from nearby Echo Island all the way to far-off Lost Bay, and begins with my boyhood mission of discovering caves in the forest.

I made a specialty of discovering and exploring “caves,” those caves created by any leaning rock, overhanging ledge, or hollow stump into which I could squeeze a portion of my body.

As I reported on my solitary explorations and discoveries there grew a concern among certain older folks that “bears live in caves,” and should Douglas really be allowed to explore them on his own? I knew that I was perfectly safe and well protected in that Grandad, over the strenuous objections of Mother and Grandmother and other Responsible Adults, had given me a brand new, mother-of-pearl-handled, Royal Canadian Mounted Police sheath knife. With this formidable weapon on my belt, I was impervious to danger, and had no doubt I could face down any bear or large carnivore I might encounter. Indeed, I looked forward to the opportunity! But it was not until Grandad made a complete inspection tour of my caves, declared them bear-free, and gave them the grandfatherly seal of approval that the concerns abated. Somewhat.

But other than these terrestrial explorations there was another place where, if the fishing boats were full, I was more likely to be found, and that was on the resort dock. The dock was an endlessly fascinating place for a number of reasons. Various sizes and types of boats came and went there all day long, bound for or returning from destinations I could only imagine, far down the blue mists of the big lake. The occupants of the boats often produced stringers of fish—golden, gleaming walleyes or mean-eyed northerns, or fantastical tales of “the one that got away.” I heard stories of sharp-fanged rocks hit or barely missed, wildlife seen, big winds and big waves and all the adventures that adults have while kids wait on docks.

But I was not merely waiting. Equipped with my Little Lake cane pole, I fished—hour after hour—trying desperately to catch more fish off the dock than the adults could catch in the boat. I often succeeded, and the fact that my fish were mostly tiger-striped perch while theirs were tiger-toothed pike in no way lessened the achievement.

And every night, as I fell asleep listening to grown-ups talk, the stories rolled forth… How I loved to listen to them, the stories of parents and grandparents and aunts and uncles—stories of family and people and life and especially of what happened on the water, in the boats, on the big lake, in the wild world between Echo Island and Lost Bay. Then, through the open window by my head, from far out on the lake, would sometimes come the haunting, echoing call of a loon¬–and with it the soft, distant calling of something more, a nameless, timeless something of which the voice of the loon was only a part.

For a boy who, for years, did very poorly in school, who suffered from a profound shyness—and ADHD and dyslexia that were not identified until decades later–these experiences on Kabetogama were life-giving. I knew that there was in the world a place more beautiful than the town where we lived. A place where I felt successful and adventurous and connected to the vital, living world around me, a place more real and authentic than the claustrophobic halls and schoolrooms where I had to spend so much of my life.

As time passed, I would eventually discover that the water trail from Echo Island to Lost Bay was only a small doorway, was in fact connected to a vast and nearly endless labyrinth of waterways that stretched and beckoned from Lake Superior north to Hudson Bay, and far to the northwest to places like Wollaston, Reindeer, Great Slave, and Athabaska. In time, trading the fishing boat for a canoe, I would explore a great deal of it, exploring life itself in the process.

I also found that many shared my feelings and longed for the same sense of freedom and deep connection as I did. I found that a life could be made of guiding, of writing, of sharing things that matter, of telling stories deep into the night. A life could be made upon a path of woods and waters.